WHAT

FUN HAVE YOU GOT LINED UP FOR TONIGHT?? We'll be posting a few

Halloween themed items today, but our PCASUK Halloween Celebrations,

with prizes, competitions and a few extras (!) kick off this Halloween

Weekend. Please join us then Here's Peter Cushing as MacGregor form 'Tendre Dracula' Have a HAPPY and SAFE Halloween!

Thursday 31 October 2013

HAVE YOURSELF A VERY HAPPY HALLOWEEN!

Labels:

dracula,

halloween,

halloween banner,

horror films.,

peter cushing,

spooky,

tendre dracula,

vampire,

witches

Sunday 27 October 2013

'NAME THE SYSTEM!' PETER CUSHING / TARKIN OUT TAKE BLOOPER FROM 'STAR WARS'

Not something you come across every day, a blooper out take featuring Peter Cushing. What's more an out take of Peter Cushing as Grand Moff Tarkin in 'STAR WARS'!

Watch the out take at our facebook acount: Here at 45 seconds in:HERE

Labels:

blackboxclub.,

blooper,

carrie fisher,

cushing,

out take,

pcasuk,

princess leia,

star wars,

tarkin

HALLOWEEN COMPETITION NEXT WEEK: FIVE COPIES OF 'LEGEND OF HAMMER VAMPIRES' TO BE WON

Look Out Next Week: We have FIVE copies of Donald

Fearney's 'Legend of Hammer Vampires' documentary dvd for you to win in a

PCASUK Halloween Competition...

Labels:

competition,

docmentary,

donald fearney,

dracula,

dvd,

halloween,

hammer films.,

hammer vampires,

legend

Friday 25 October 2013

TWENTY YEARS TODAY: VINCENT PRICE ANNIVERSARY

Good Morning all. As you go about your day

today, spare a place in your heart to remember, a king. It's twenty

years ago today that Vincent Price sadly left us. Here's some charming

behind the scenes pics of Vincent Price and Peter Cushing after their

filming their titanic 'ding-dong' in MADHOUSE in 1974, one of the few

times that they worked together.

Labels:

amicus,

anniversary,

behind the scenes,

devil day,

dr death,

madhouse,

paul toombes,

the black box club,

twenty years.,

vincent price death

Wednesday 23 October 2013

TROY HOWARTH 'CURSE OF FRANKENSTEIN' REVIEW AND LOBBY CARD GALLERY

Sometime in the 1950s, American writer/producer Milton

Subotsky (later to head Hammer's rival, Amicus) approached Hammer with

the idea of doing a remake of James Whale's Frankenstein. Producer

Anthony Hinds didn't think much of the idea and rightly reckoned that

any infringement on the material as established in the earlier versions

of the 30s and 40s would bring the legal eagles at Universal Studios

swooping down on Hammer. Hinds saw potential in completely ignoring the

earlier versions, however, and decided to entrust screenwriter Jimmy

Sangster with delivering a fresh adaptation of Mary Shelley's classic

novel. In 1956, Sangster was still a "lowly" production manager, but he

pitched an idea that Hinds liked, and was given the chance to write his

first script, for the Quatermass

knock-off X The Unknown. Hinds recognized that Sangster had talent as a

writer and, better still, he also had a practical understanding of the

limitations of Hammer's resources. He could be relied upon to deliver a

filmable script which wouldn't stretch the company's coffers too far.

Frakenstein would be Sangster's sophomore effort as a writer, and the

final result would have undreamed of repercussions for just about

everybody connected with the project.

Whereas the Universal series highlighted the character of

the monster - played in the first three films by Boris Karloff, but then

reduced to lesser actors with mixed results for the remaining sequels -

Sangster decided to focus his energies on the character of Frankenstein

himself. It's a common misconception,

created in large part by Universal themselves, that Frankenstein is the

monster, whereas in fact, he is actually the creator himself. Sangster ignored Shelley's conception of an

earnest, well-intended medical student who overstretches his bounds by

attempting to create life. Instead, he

recreated the character as a Byronic dandy with a sadistic streak. The monster and the creator were to become

one, in essence.

Hinds was thrilled with Sangster's efforts and assembled a

dream team to realize his vision. Director Terence Fisher later

maintained that he was owed a project by the company, but Hinds would

contradict this, stating that he knew he was the best man for the job

and would have hired him regardless. Fisher's career up to that point

was not terribly distinguished: a long string of low budget potboilers

with little to distinguish them from the "quota quickie" pack, though he

did helm a few fine pictures like Portrait from Life and So Long at the

Fair. He had also directed Hammer's earliest brushes with sci-fi and

fantasy, Spaceways, Four Sided Triangle and A Stolen Face, and the

thematic concerns of those films would be reflected here. Fisher proved

to be a natural for the

Gothic; by his own admission, he was not a fan of the genre at the time

and had not seen the original Universal horrors, and he even rejected

invitations to see them, hoping to keep his own approach fresh and

uninfluenced by what had come before. He was wise to do so, as his

matter-of-fact, down-to-earth approach helped to make this a very new

kind of horror film. Fisher was also given a crew that would help to

define the look and style of Hammer horror: cinematographer Jack Asher,

production designer Bernard Robinson, camera operator Len Harris, editor

James Needs, composer James Bernard, etc.

To head the cast, Hammer elected to ignore their

long-standing policy of importing a faded American name for marquee

value. This was to be a very British horror film, and only a British

actor could do it justice. Hinds turned to Peter Cushing, then the

biggest TV star in the country, who surprised by the producer by

enthusiastically accepting the project. Cushing would subsequently

weigh the pros and cons of doing further films for the studio, rightly

recognizing that being associated with genre fare might impact his

chances of getting more "serious" film work, but he eventually decided

to embrace the steady flow of work, and a horror icon was born.

To play the creature (no longer referred to as the monster,

lest Universal's lawyers get tetchy about it), Hinds initially turned

his eye to imposing comic actor Bernard Bresslaw. In the end, however,

they decided to go with bit part player Christopher Lee. Standing 6'5"

in height, Lee also had background in mime, which would come in very

handy given that the role was mute. Lee suffered under the hands of

makeup artist Phil Leakey, who was challenged with the task of devising a

new monster makeup design. His early sketches ranged from the bizarre

to the ludicrous, with Lee imploring that it should just look like a

jigsaw puzzle as he's been stitched together from various body parts.

The final makeup drew jeers from fans accustomed to Jack Pierce's iconic

Karloff

design, but it has stood the test of time and is every bit as effective

a piece of work in its own way.

Finally released to cinemas as The Curse of Frankenstein,

the film was the first Gothic horror to be filmed in color - and the

added bonus of some then-graphic gore and an emphasis on busty women in

cleavage-hugging period gowns outraged critics and tickled audiences.

Seen today, The Curse of Frankenstein remains one of

Hammer's finest films. Fisher directs with a sure and steady hand. The

characterization of the Baron it matched by Peter Cushing's superb

interpretation. Lee's creature is at once pitiable and genuinely

frightening; it is most assuredly one of his most under-valued

performances. The production values are solid and belie the film's low

budget. It also set the style for everything which would follow and did

so in a way that seems far more sure-footed than it probably should.

The character would be revisited in a series of sequels,

with Cushing appearing in all but one of them - that one being an

ill-advised parody of sorts, The Horror of Frankenstein (1970), starring

Ralph Bates. Sangster would pen the first follow-up, The Revenge of

Frankenstein (1958), while Hinds himself handled writing chores on most

of the other entries. Ironically, it was the Hinds and Sangster-free

Frankenstein Must Be Destroyed (1969), written by Bert Batt, which would

mark the series' high watermark. The various writers brought different

interpretations to bear on the character of the Baron, making it

impossible to view the series as one long-running saga, but Cushing's

commitment to the role made the films a delight. The Curse of

Frankenstein may not be as audacious as

some of the later entries, but it still remains one of the best of the

lot - and a classic slice of Hammer horror.

Appropriately enough, the film was the first of the initial

Hammer Gothics to hit blu ray through Icon and Lionsgate. Their Region

B/Region 2 blu ray/DVD combopack was met with much derision, however,

owing to a flawed transfer. Word has it that a 4K master was provided

by Warner Brothers, but Hammer failed to capitalize on the format's

capabilities by cleaning up the image and going for a sharper, better

defined image. As is so often the case with these controversies,

however, the extreme reactions are a bit over the top. While the

presentation is far from definitive and will never be used as a

reference quality disc for showing off the capabilities of the medium,

it's still quite watchable - especially in the full frame transfer which

restores some information missing in

the 1.66 version which was also included. Colors are a bit pale and

the image isn't as sharp as one would like, but it marks an improvement

over the DVD edition from Warner Bros and restores a shot which had been

censored for many years (you'll know it when you see it). The disc is

also overflowing with extras, including an informative and entertaining

commentary by Jonathan Rigby and Marcus Hearne and a wonderful

featurette about Cushing.

Review: Troy Howarth

Images: Marcus Brooks

Labels:

bandages,

blu ray,

hammer horror,

hazel court,

laboratory,

lobby cards,

mary shelley,

peter cushing,

the black box club.

Sunday 20 October 2013

'DON'T STOP ME NOW' GREAT YOUTUBE CUSHING FRANKENSTEIN TRIBUTE

Labels:

cushing tribute,

don't stop me now,

freddie mercury.,

queen,

you tube

CONGRATULATIONS SIR CHRISTOPHER LEE : BFI FELLOWSHIP : PHOTOS AND CLIP

Hammer horror star Sir Christopher Lee said it was a "very emotional moment" when he received his British Institute Fellowship from his friend Johnny Depp.He tearfully accepted the award at the London Film Festival, saying: "I didn't know you were going to be here. I must try and pull myself together."

Sir Christopher, 91, who described receiving his award as "a great joy", is famed for his villainous portrayals of Bond bad guy Scaramanga and evil wizard Saruman in The Lord of the Rings.

He has amassed more than 250 screen credits, including The Wicker Man, The Man with the Golden Gun and more recently, several Tim Burton films including Sleepy Hollow, which starred Depp. He also played Count Dooku in the Star Wars prequels.

Depp, who sneaked into the awards ceremony to surprise his friend, said it was his "great honour" to present the award to "a very great man", saying he had been "fascinated and inspired" by him

"He's been a wonderful individual and over the years I've had the pleasure of working with him and it has been a childhood dream come true," he said. "But as great as it is to work with him, that pleasure doesn't compare with getting to know him and being able to count him as a true friend.

"A national treasure and a genuine artist. I love ya!"

Sir Christopher responded by saying: "I can't thank you enough," in reference to Depp, who he had been told could not make the occasion as he was elsewhere. He went on : "When I take a look back, and it's a long one, 67 years, at the characters I've played I get a truly strange feeling they were all played by somebody else, and not by me. "And there are a few occasions when it has been the case I wish it had!" He said of Depp: "He means an enormous amount to me. He is one of very few young actors on screen today who's truly a star. "Everything he does has a meaning. He's a joy to work with, an actor's dream and certainly a director's dream. I could go on a long time but I'd probably embarrass him."

Johnny Depp presents Sir Christopher Lee with his British Film Institute Fellowship Award : Depp on Sir Christopher Lee: " A national treasure and a genuine artist. I love ya!"

Watch Sir Christopher Lee presentation at BFI evening. HERE

http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/entertainment-arts-24600683

Labels:

bfi,

british film institute,

fellowship award,

fellowship award.,

johnny depp,

love you,

national treasure,

saruman.,

scaramanga,

Sir christopher lee

Saturday 19 October 2013

HAPPY BIRTHDAY MEGAERA: HAMMER FILMS THE GORGON HITS 49

Today marks the UK release of Hammer Films

'THE GORGON' 49 years ago today. Happy Birthday, Megaera! Thanks to Josh

(Gorgon-Super Fan) Kennedy, for the reminder! Here's our feature on

the life of actress who actually played her with gallery: http://petercushingblog.blogspot.co.uk/2013/01/kb-zorka-on-life-and-career-of-prudence.html

Labels:

anniversary,

birthday,

bray studios,

cushing,

fisher.,

hammer horror,

lee,

the gorgon

Thursday 17 October 2013

GUSTAV WEIL AND THE TWINS OF EVIL: SCREEN SAVER

Labels:

collinson twins,

hammer horror,

john hough,

madeline colllinson,

mary collinson,

peter cushing,

twins of evil,

vampire twins,

witch burning.

HOW WE COUNTED DOWN THE DAYS: HAMMER FILMS THE MUMMY BLU RAY

Labels:

blu ray,

christopher lee,

hammer films,

icon films,

john banning,

jonathan rigby,

marcus hearn.,

peter cushing,

the mummy

EIGHT PUBLICITY PHOTOGRAPHS: 'FRANKENSTEIN AND THE MONSTER FROM HELL'

Labels:

asylum.,

dave prowse,

hammer horror,

madeline smith,

peter cushing,

shane briant,

terence fisher

Tuesday 8 October 2013

JUST SIX DAYS TO GO. . .

Labels:

christopher lee,

Egypt,

hammer films,

icon films,

mummification.,

mummy,

pharaohs curse,

reincarnation,

tombs

Sunday 6 October 2013

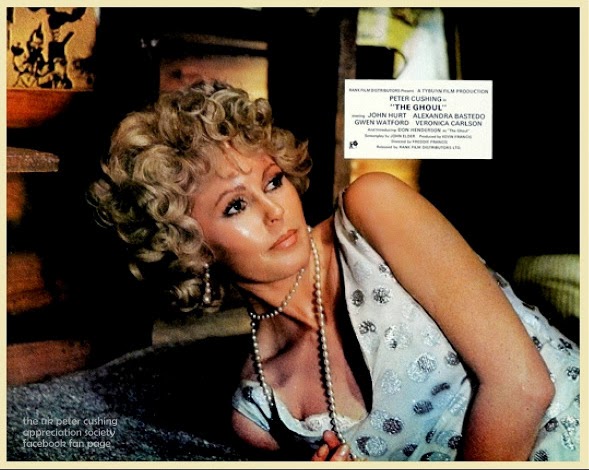

MATTHEW CONIAM ASKS: WHERE IN HEAVEN'S NAME IS 'THE GHOUL' ? FEATURE AND GALLERY

Every year I spend a week at an inn just inland of Land's End and most mornings I get up at 5 and enjoy the lonely cliff walk to England's most southerly point as dawn rises. It is eerily quiet, the whistling wind the only sound, and dozens upon dozens of rabbits the only living things in sight.

I’d like to say I spend most of my time on these walks pondering the deep mysteries of existence and the universe, and it’s true, when the first rays of the sun hit those timeless rocks, standing now just as they have through the whole history of human life in this most primitive and inspiring of lands, I do have my moments. But by and large, I’ll be honest, I’m thinking about The Ghoul.

I really can’t decide if it’s that I can’t leave this film alone, or that it can’t leave me alone, but I seem to have written more about it, and more often, than any other movie. A review of the mid-nineties video release was my first ever professionally published piece of writing. (Where did those two decades go?) And I still watch it several times a year, with undimmed pleasure.

Why the obsession? On the one hand, I am one of those people who tend toward the less well-travelled byways of the British horror film. I love the Hammer classics as much as anyone, but apart from the footnotes, that work’s been done. I prefer to scratch beneath the surface of the more obscure or underrated branches of the family tree. I’ve always thought the Tyburn story, for instance, should be of interest to anyone interested in Hammer or British horror, regardless of whether they think the films themselves were great, okay or terrible, yet it remains curiously overlooked.

That said, there’s also the very simple fact that The Ghoul really is my favourite British horror movie of them all. And ever since the opening scene scared the life out of me and sent me scampering out of the room as a little boy, it has seemed to me the quintessential British horror movie, so crammed with things to love.

I’ve never really got to grips with why so many seem to have at best little regard for it, and often a belligerent dislike. But while hardly anyone in print seems to have a good word to spare, I know from experience that it has a huge following among fans, who clamour for a DVD or BluRay release, and love its unique mixture of old-fashioned shivers and forward-looking mayhem. Why the published authorities fall so squarely in one half of the love/hate divide is a question worth considering, but what is in no doubt is that they are certainly misrepresenting their constituency.

I have already done my best to make a case for the film elsewhere on this site, (as well as detailed my thwarted attempts as an undergraduate to get Kevin Francis to discuss it with me in detail). This time I want to do something different, and take you back to those Cornish cliffs, not to attempt to persuade the undecided as to its merits, but to elaborate on a few of the questions the film throws out to those of us who already love the movie.

Most of them would never occur to the casual or first-time viewer, but they nag incessantly if you’re a devotee. The central mythos itself is incredibly vague: we know that some unholy sect ‘corrupted’ Cushing’s son Simon, and that he is now the Ghoul as a result, but we don’t know if this was achieved by supernatural means, or disease, or merely moral corruption. We don’t even know if the Ghoul is compelled to eat human flesh by necessity or choice.

Most of them would never occur to the casual or first-time viewer, but they nag incessantly if you’re a devotee. The central mythos itself is incredibly vague: we know that some unholy sect ‘corrupted’ Cushing’s son Simon, and that he is now the Ghoul as a result, but we don’t know if this was achieved by supernatural means, or disease, or merely moral corruption. We don’t even know if the Ghoul is compelled to eat human flesh by necessity or choice.

Our first instinct, I would guess, is to assume that it is by necessity, but the more you ponder that the harder it becomes to square with the events of the film. Does the household rely purely on stranded travellers to provide him with food? (There seems to be a reasonably large collection of undergarments under Tom’s pillow, after all.) Would that really be a frequent enough occurrence, and wouldn’t suspicion soon fall upon them? Would his system really know the difference if they brought him pork chops? And does he eat only women – if not, why leave the body of Billy in his crashed car?

Of course, for many fans, the real mystery of The Ghoul is why it’s so damned hard to see these days. Mired in copyright hell, the entire Tyburn back catalogue is officially out of bounds, with audiences having to rely on poor quality imported dupes, old tapes or off-air recordings. That mid-nineties VHS release marked the last time it was ever made officially available to the home market, and while it was a late-night horror staple in my television childhood (and even on one occasion made the cover of the Radio Times) it has not been seen on British TV since 2007.

For those who may only be familiar with one version, the differences are all in the first half. Several trims have been restored to the party scenes, with the biggest surprise for those who, like me, knew the original version by heart being when the opening prank scene continues for another minute after Alexandra Bastedo’s scream. But the most significant extra portions occur in the scenes with Veronica Carlson’s Daphne after her arrival at Lawrence’s house: it is this version and this only that includes her famous bath scene. (Stills from this sequence were used extensively in promotion and front of house materials, yet it would seem the sequence had never actually been seen by audiences before the mid-nineties.)

That 20s setting is one reason why I love the film, and not just because it happens to be an era that entrances me anyway; it’s also bafflingly underused as a backdrop to traditional horror, and I’d be interested to know how early in the project’s gestation it was settled on. It’s often stated (including by me in my earlier piece on this site) that it was adopted somewhat arbitrarily, to make use of sets from The Great Gatsby left over at Pinewood, but now I’m not so sure. For one thing, the post-war ‘lost generation’ theme is central to the thematic structure in a way that doesn’t feel at all grafted on, and for another, only the opening scene actually uses roaring twenties settings, and that’s all filmed at Heatherden Hall, a real and permanent building on the grounds of Pinewood. Doubtless spare set dressings and costumes were gratefully received from Gatsby, but surely not deemed valuable enough in themselves to influence something so fundamental to the movie a priori.

Another vexed issue for hopeless obsessives like me is just where the film is set.

Now,

some films tell you where they are set and some films don’t: no big

deal. But The Ghoul is intriguing because it has two very clear and

distinct locations: a fashionable society party and a fog-shrouded moor,

neither of them actually named, and one named landmark: Land’s End, the

ultimate destination of the car race that lands the four heroes in the

Ghoul’s lair.

I had always lazily assumed that it was indeed in the vicinity of

Land’s End that they meet their fates (and always liked to think that

the large, somewhat eerie, strangely melancholy white house I pass on my

Land’s End walks, all alone in extensive but featureless grounds, was

the abode of Mr Lawrence and his oddball household!) I

also assumed, even more lazily as it turns out, that they started from

London, and was frankly amazed, when I double-checked, to learn that

both assumptions are completely

unsupported by anything in the film itself. The only assistance we are

given is the observation that Land’s End is “over a hundred miles” from

where they begin, immediately corrected to “more like two.”

So we can have some fun here: Four people in the 1920s are attempting to

drive to Land’s End. Let us suppose that they live in a reasonably

large town, given their wealth, awareness of fashions in an age of

limited media, and the large number of like minds attending their

parties. Their destination is between one and two hundred miles from the

start point, and somewhere, along the shortest and most reasonable

pre-motorway route, they pass through boggy moorland and become

stranded. (Since both cars separately end up there, it is reasonable to

suppose that neither took a wrong turning.) So where do they end up, and

where have they probably started from?

Not London, surely? Land’s End is around 264 miles from London as the

crow flies, and at least 300 miles (and five hours) by car, even with

modern roads and speeds. Now, if you draw two circles on a map, one

representing 100 miles from the radial point of Land’s End and the other

two hundred, and assume that the start point must be a large-ish town

somewhere within those two circles, the range of possibilities is

surprisingly small. The most likely candidates (from a shortlist that

also includes Bournemouth, Yeovil and Salisbury) are Southampton,

Bristol and Bath. (Since I live there, I prefer to opt for Bath.)

Now, where do they end up? The moors on that route are Exmoor or

Dartmoor if they don’t even get to Cornwall, Bodmin Moor or Goss Moor if

they do, and Bodmin Moor (substantially larger than Goss Moor and an

appropriately misty, marshy and mysterious place steeped in folklore and

legend) would I think be the more likely to have a secluded country

mansion in the middle of nowhere within it. (Not sure that any of its

inhabitants needed to sleep inside mosquito nets, even in the 1920s, but

we’ll allow Anthony Hinds that much dramatic license.)

So that was my official guess: Bath to Bodmin, and with the film not

telling, I assumed I was safe enough from dissent. But when I presented

all this hard-thought reasoning in a blog post last year, a reader

reminded me that there is also a novelisation of the film by Guy Smith,

and that it has a little more detail on these matters. Having at last

obtained my own copy, I took it with me to Land’s End this year. The

good news is that it does indeed go into this and other of the film’s

enigmas in greater detail: the bad news is that it makes them even more

confusing.

First, and despite all of the above, there are several references that

suggest the characters are indeed from London. Even though Smith

replaces Geoffrey’s mere guess of two hundred miles with Daphne stating

it as a certainty, he later has both Daphne and Angela wishing to

themselves that they were “back in London”, and includes two dialogue

references: Lawrence suggests that Daphne “will be able to journey back

to London” after she has rested, and Geoffrey speculates that Angela

might “try and walk it back to London out of sheer cussedness.”

So on the face of it, it’s all looking rather bit bleak for my deductive

reasoning! Or are there grounds for thinking that this was Smith’s own

invention rather than derived from the original script? After all,

hardly any of Smith’s dialogue has no parallel at all in the dialogue of

the film, and the greater part of it is verbatim - but it’s a fact that

both Lawrence’s and Geoffrey’s spoken references to London occur only

in the book. Even more tellingly, a later exchange that does occur in

both has been subtly altered by Smith: when Geoffrey is enquiring as to

Daphne’s whereabouts, Lawrence tells him that she said “she was going to

return to London”, to which Geoffrey replies, “It’s likely.” Smith

normally sticks closely to the film, as I said, but in the film Geoffrey

asks Lawrence where she had gone and Lawrence replies, with some

diffidence, “She did say London.” In other words, far from knowing she

would be intending to return there, it is as if he is nervously making a

Westcountry recluse’s best and most obvious guess as to where a dazzler

like Daphne might have originated from, and hoping he hasn’t given

himself away in the process. And rather than “It’s likely”, Geoffrey’s

reply is an incredulous “London?” - implying that it is, on the

contrary, somewhat unlikely. It seems reasonable to speculate that the

pinpointing of London is all Smith’s work, and he has tinkered with this

exchange so as to accommodate it.

As to where they end up, again Smith has a surprise in store, though

this time he only states it once: “Dawn was breaking as the Vauxhall

reached Dartmoor.” But Dartmoor is in Devon, a long way from where they

had hoped to arrive, and therefore it seems unlikely that both cars

would have ended their journeys there. Once again, with its Hound of the

Baskervilles connotations, Dartmoor would be an understandable casual

choice for someone who was simply wanting to come up with a likely

Westcountry moor: again, it feels more like Smith than Elder.

As well as definite locales, we are additionally given a definite date

of 1923 – just a tad early, I’d have thought, for the twenties to be

quite as roaring as we see them in the first scenes (especially in the

provinces). It also makes Daphne considerably younger than we might have

assumed from her conversation about faking her age so as to drive

ambulances during the First World War.

So where did Smith get all this inside info? The absence in the book of

any of the material in the extended video cut, and in particular the

compression of time that follows from the deletion of Daphne’s bath and

surrounding sequences, hints that he may even have been working to

viewings of the film itself. (A coincidence, otherwise, given that all

those scenes were scripted and shot, that both he and the film editors

made the same cuts independently.) On the other hand, his omission of

Lawrence’s lines about he and his late wife “still being together” (an

ill-fitting addition to the scene that is obviously the work of Cushing

himself) suggests he is working to the script.

If so, is the most substantial chunk of new material in the book – a

grim sequence detailing the removal and dismembering of Daphne’s body

after her murder, to be found in no extant version of the movie –

Smith’s own invention, or a discarded fragment of an earlier script? It

reads like Smith consciously upping the gore quotient a little, but

Elder was surprisingly fond of such outré flourishes, and often had to

be held in check by censors both internal and external.

The only thing to do was check with Guy N. Smith himself, so I got in

touch with the venerable horror author – whose tales of deadly crabs

were as familiar a component of the locker rooms of my school days as

unwashed PE kits and packets of Monster Munch – to put these matters to

him.

“I was approached by Sphere Books and Pinewood Studios,” he

recalled; “I went to Pinewood where a showing of the film was arranged

and was given a film script. I wrote it in three weeks, delivered the

finished manuscript to Kevin Francis and that was that.”

And while, with forty years distance between him and the project, he

could sadly no longer confirm if the locations were settled by him or

not, he was adamant that there was no room for him to have any major

narrative input: “I was not free to add elements of my own: the novel

had to follow the film throughout, so the (dismemberment) sequence you

mention would have been supplied.”

If Smith is really not to be credited with any improvisation at all,

then the book very usefully sheds light on some of those questions of

plot and logic I mentioned earlier.

For instance, the impression I got from the film was that the main instigator was Cushing’s Lawrence, bound by an oath to his late wife, reluctantly but nonetheless actively enticing victims to the house. The Ayah, though the one tasked with the job of preparing the carcasses and feeding the Ghoul, seems devoted principally to Lawrence, and both appear to be acting only under compulsion.

True, there is one line in the film where she says that is her prayers that brought Daphne and Angela to the house, but it is much clearer in the book that she really does mean this, and even more strikingly, there is the clear implication that Lawrence is to some extent left in the dark as to exactly what goes on, and would react more forcefully in opposition were it otherwise:

Every so often she stopped and listened. Each time she breathed a long

sigh of relief as she heard the violin music in the study. Mr Lawrence

would not tolerate her rites. Her prayers would be interrupted, and,

today of all days, that must not happen.

There is of course that one moment in the film where Lawrence makes a

big show of disrupting her ritual, but the clear implication of that,

surely, is that he is putting on an act for Geoffrey, to imply that it

has nothing to do with him. The book, by contrast, seems to want us to

think his anger and surprise were genuine. But how could they be?

There seems to be a suggestion that he succumbs periodically to the

power of the Ayah’s prayers, and is unable to stop himself acting as she

wishes while under their influence, as when his playing of a Bach

sonata gradually mutates into something else while she is chanting:

It was an Oriental theme, so much in keeping with her own mood, almost

as though she was in telepathic contact with her master. The gods were

on her side. They were exerting their powers over Lawrence. Surely now

he understood what had to be done. He would not stand in her way.

A couple of minutes later she peered cautiously round the kitchen door

into the hall. It was deserted. It was necessary to move with even

greater stealth now that a new day had dawned. The study door was open.

She glanced in, and then drew back swiftly as she saw Lawrence. Her

heart pounded madly. If he should come into the hall, and catch her with

this in her hands…

So what does he think happens to the people he knowingly brings into

harm’s way, and conspires with both Tom and the Ayah to prevent from

leaving? Unless my reading of it is an extremely idiosyncratic one, none

of this comes across in the movie at all. His behaviour never seems

controlled externally; though tormented he seems nonetheless plainly

devious and culpable.

Just another mystery for us to ponder!

(Thanks to Guy N. Smith for indulging me.)

Written by:Matthew Coniam

Images: Marcus Brooks

Labels:

alexandra bastedo,

anthony hinds,

cannibal.,

cornwall,

desolation,

fog,

guy n smith,

ian mcculloch,

john elder,

john hurt,

lends end,

peter cushing,

the ghoul,

tyburn films,

unlimited photographs

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)